Contents

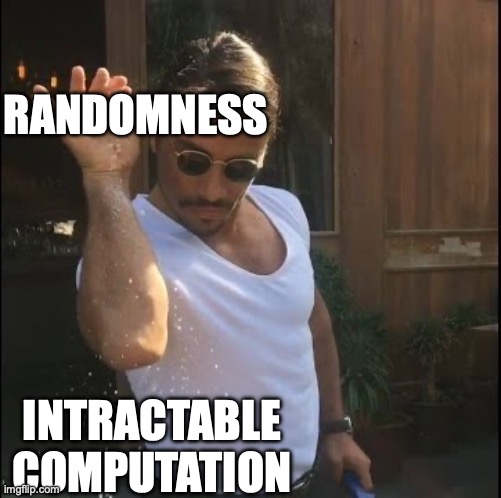

Sometimes when you deal with complicated computations, either because of the input size or the complexity of the computation, you cannot get an answer in any feasible amount of time, no matter how much computational power you have.

When the limits of tractability are reached, we can give up deterministic computation and embrace randomness to get an answer in a much more reasonable time.

This is the case of Monte Carlo methods, which are a class of algorithms that use random sampling to solve mathematical problems. And, of course, like everything nice in math and computer science, it has the Von Neumann’s fingerprints all over it. Alas, that is a story for another post, that I already covered in “Von Neumann: the Sharpest Mind of the 20th Century”.

I was recently skimming over a textbook that I used to use

in my undergraduate course on probability theory [MiUp17]The PDF is freely available here.

,

and I stumbled upon a very interesting algorithm for calculating the median of a list.

By the way, this textbook has one of the best covers in math textbooks. It is Alice in Wonderland dealing with a combinatorial explosion, see it below:

The algorithm uses sampling to probabilistically find the median,

and uses Chebyshev’s inequality,

an upper bound on the probability of deviation of a random variable from its mean.

Since it is a probabilistic algorithm,

it finds the median in (linear time) with probability

(close to for large ).

Note that for any deterministic algorithm to find the median,

it needs to sort the list, which takes (linearithmic time)

on average or (quadratic time) in the worst caseNote that I am comparing against quicksort since it uses space,

whereas merge sort would use space with the worst case is .

.

You can always iterate and run the algorithm until you get a result,

but now the runtime is non-deterministic.

The nice thing about the algorithm is that Chebyshev’s inequality

does not makes assumptions about the distribution of the variable,

just that it has a finite variance.

This is excellent since we can move away from the lala-land of

normal distributions assumptions that everything is a Gaussian bell curveFor my Bayesian rant,

see “Lindley’s Paradox, or The consistency of Bayesian Thinking”.

.

Chebyshev’s Inequality

Chebyshev’s inequality provides an upper bound on the probability of deviation of a random variable (with finite variance) from its mean.

The inequality is given by:

where is a random variable, is the mean, is the standard deviation, and is a positive real number.

This is a consequence of the Markov’s inequality, and can be derived using simple algebra. The reader that is interested in the proof or more details, see the Wikipedia pages linked above.

Because Chebyshev’s inequality can be applied to any distribution with finite mean and variance, it generally gives looser bounds compared to what we might get if we knew more about the specific distribution. Here’s a table showing how much of the distribution’s values must lie within standard deviations of the mean:

| Min. % within standard deviations | Max. % beyond standard deviations | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0% | 100% |

| 50% | 50% | |

| 2 | 75% | 25% |

| 3 | 88.8889% | 11.1111% |

| 4 | 93.75% | 6.25% |

| 5 | 96% | 4% |

| 10 | 99% | 1% |

For example, while we know that for a normal distribution about 68% of values lie within one standard deviation, Chebyshev only tells us that at least 0% must lie within one standard deviation! This is the price we pay for having a bound that works on any distribution. Yet, it is still a very useful bound.

Randomized Median

Alright, now let’s see in practice how this works. Below is the algorithm for finding the median of a list, as described in algorithm 3.1 in the “Probability and Computing” textbook:

Input: A set of elements over a totally ordered universe.

Output: The median element of , denoted by .

- Pick a (multi-)set of elements in , chosen independently and uniformly at random with replacement.

- Sort the set .

- Let be the th smallest element in the sorted set .

- Let be the th smallest element in the sorted set .

- By comparing every element in to and , compute the set and the numbers and .

- If or then FAIL.

- If then sort the set , otherwise FAIL.

- Output the th element in the sorted order of .

As you can see, the algorithm starts by sampling a set of elements from the list, sorting them, and then using the sorted elements to find the median. How it finds the median is by using the set , which is the set of elements in that are between and , where is the lower bound and is the upper bound of the sampled set .

The algorithm’s brilliance lies in its probabilistic guarantees. It can fail in three ways:

- Too few sampled elements are less than the true median

- Too few sampled elements are greater than the true median

- The set becomes too large to sort efficiently

However, the probability of any of these failures occurring is remarkably small: less than . This means that as the input size grows, the chance of failure becomes increasingly negligible:

- For n = 10,000: failure probability ≤ 0.1

- For n = 1,000,000: failure probability ≤ 0.032

- For n = 100,000,000: failure probability ≤ 0.01

When the algorithm doesn’t fail (which is the vast majority of the time), it is guaranteed to find the exact median in linear time. This is achieved by carefully choosing the sample size, , and the buffer zone around the median, , to balance between:

- Having enough samples to make failure unlikely

- Keeping the set small enough to sort quickly

The algorithm provides two important guarantees:

Correctness: The algorithm is guaranteed to either FAIL or return the true median. This is proven using Chebyshev’s inequality in two steps. First, we show that the true median will be in set with high probability:

- Let be the count of sampled elements ≤ in

- When , we call this event

- Let be the count of sampled elements ≥ in

- When , we call this event

- When , we call this event

- By Chebyshev’s inequality, each event has probability at most

Second, we show that when is in , we find it:

- counts elements < , so there are exactly elements between and

- Therefore, must be the th element in the sorted

- Let be the count of sampled elements ≤ in

Linear Time: The algorithm runs in time when it succeeds because:

- Sampling and sorting takes time

- Comparing all elements to and takes time

- Sorting takes time since

- All other operations are constant time

Why These Guarantees Work

The key to understanding why this algorithm works lies in analyzing the probability of failure. Let’s look at how we bound the probability of having too few samples below the median (event ):

For each sampled element , define an indicator variable where:

Since we sample with replacement, the are independent. And since there are elements ≤ median in , we have:

Let count samples ≤ median. This is a binomial random variable with:

- Expected value:

- Variance:

Using Chebyshev’s inequality:

This shows that both events and have probability at most , and also that has probability at most :

All these events combined demonstrate that the algorithm rarely fails: the probability of having too few samples on either side of the median decreases as , becoming negligible for large . If higher reliability is needed, you can simply run the algorithm multiple times, as each run is independent.

Haskell Implementation

I implemented the algorithm in Haskell, because I stare at Rust code 8+ hours a day, and I want programming in a language that “if it compiles, it is guaranteed to run”. The only other language apart from Rust that has this property, and some might say that it is the only language that has this property, is Haskell.

The code can be found on GitHub at storopoli/randomized-median.

So let’s first go over the vanilla, classical, deterministic median algorithm:

median :: (Ord a, Fractional a) => [a] -> Maybe a

median [] = Nothing

median xs =

-- First convert list to array for O(1) random access

let n = length xs

arr = listArray (0, n - 1) xs

-- Sort the array elements

sorted = sort (elems arr)

sortedArr = listArray (0, n - 1) sorted

mid = n `div` 2

in if odd n

then Just (sortedArr ! mid)

else Just ((sortedArr ! (mid - 1) + sortedArr ! mid) / 2)First we define a function signature for the median function:

it takes a list or elements of some type that is an instance of both the Ord type class,

and the Fractional type class.

This is because we must assure the Haskell compiler that the elements of the list can be

ordered and that we can perform fractional arithmetic on them.

It returns a Maybe a because the median is not defined for empty lists.

The Maybe type is an instance of the MonadYes M word mentioned.

If you want a good introduction to Haskell functors, applicatives, and monads,

see “Functors, Applicatives, And Monads In Pictures”

type class,

which allows us to use the >>= operator to chain computations that may fail.

It can take two values Nothing or Just a, where a is the type of the elements of the list.

For the case of an empty list, we return Nothing.

For the case of a non-empty list, we convert the list to an array,

sort the array, and then find the median,

returning the median as a Just value.

Now, let’s implement the randomized median algorithm:

randomizedMedian :: (Ord a) => [a] -> Int -> Maybe a

randomizedMedian [] _ = Nothing

randomizedMedian xs seed =

let n = length xs

arr = listArray (0, n - 1) xs

-- Step 1: Sample n^(3/4) elements with replacement

sampleSize = ceiling (fromIntegral n ** (3 / 4))

gen = mkStdGen seed

indices = take sampleSize $ randomRs (0, n - 1) gen

-- Step 2: Sort the sample

sample = sort [arr ! i | i <- indices]

sampleArr = listArray (0, length sample - 1) sample

-- Step 3: Find d (the lower bound element)

dIndex = floor (fromIntegral n ** (3 / 4) / 2 - sqrt (fromIntegral n))

d =

if dIndex >= 0 && dIndex < length sample

then sampleArr ! dIndex

else error "Invalid d index"

-- Step 4: Find u (the upper bound element)

uIndex = floor (fromIntegral n ** (3 / 4) / 2 + sqrt (fromIntegral n))

u =

if uIndex >= 0 && uIndex < length sample

then sampleArr ! uIndex

else error "Invalid u index"

-- Step 5: Compute set C and counts

ld = length $ filter (< d) xs

lu = length $ filter (> u) xs

c = sort $ filter (\x -> d <= x && x <= u) xs

-- Step 6 & 7: Check failure conditions

halfN = n `div` 2

in ( if ((ld > halfN || lu > halfN) || (length c > 4 * sampleSize)) || null c

then Nothing

else

( let targetIndex = halfN - ld

in if targetIndex >= 0 && targetIndex < length c

then

-- Step 8: Output the median

Just (c !! targetIndex)

else

Nothing

)

)I’ve added comments to the code with respect to the algorithm steps. First, the function signature is almost the same as the deterministic median function. There are two differences:

- The elements of the list does not need to be a

Fractionaltype. - We now take an additional parameter,

seed, which is the seed for the random number generator. This is needed since we are using a random number generator to sample the elements from the list.

As before, for the case of an empty list, we return Nothing.

For the case of a non-empty list, we first convert the list to an array,

and then sample n^(3/4) elements from the list with replacement.

We use the randomRs

function to generate a list of random indices,

it generates an infinite list of random values within the specified range

(in this case, from 0 to n-1),

hence sampling with replacement.

Then, we take the first n^(3/4) elements from the list.

Next, we sort the sample and convert it to an array.

Next, we find the lower and upper bounds of the sample.

We do this by finding the index of the element at position n^(3/4)/2 - sqrt(n)

and n^(3/4)/2 + sqrt(n) in the sorted sample.

We then take the element at these indices as the lower and upper bounds.

Then, we compute the set and the counts and . We do this by filtering the list with the lower and upper bounds.

Next, we check if the set is too large to sort efficiently.

If it is, we return Nothing.

Otherwise, we sort the set and find the median.

Results

Here’s the result by running the algorithm against a randomly shuffled list of contiguous integers from 1 to 10,000,001 using the magical number 42 as the seed of our random number generator. As you can see both the exact and randomized median algorithms find the right median value:

since is odd, the median is the element at position .

============================

Testing with 10_000_001 shuffled elements

Exact median calculation:

Result: 5000001.0

Time: 18.906611 seconds

Randomized approximate median calculation:

Result: 5000001.0

Time: 1.095511 seconds

Error percentage: 0.0000%

Speedup factor: 17.26xThe randomized median algorithm for the case of is at least 17x faster than the exact median calculation. That is an order of magnitude improvement over the deterministic median algorithm.

Conclusion

I love the inequalities of the Russian school of probability, Markov, Chebyshev, etc., since it does not depend on any underlying distributional assumptions. Chebyshev’s inequality depends on the random variable having a finite mean and variance, and Markov’s inequality depends on the random variable being non-negative but does not depend on finite variances.

Assuming that the underlying variable has finite variance is a reasonable assumption to make most of the time for your data. To be fair, there are some random variables that can have infinite variance, such as the Cauchy or Pareto distributions, but these are extremely rare for you to cross paths with.

Another thing to note is that instead of the Chebyshev’s inequality, we could have used the Chernoff bound to get a tighter bound on the probability of failure. But that is “left as an exercise to the reader”.

Finally, if you are intrigued to see how powerful these inequalities can be in probability theory, I highly recommend Nassim’s Taleb technical book “Statistical Consequences of Fat Tails: Real World Preasymptotics, Epistemology, and Applications” [Tale22] which is freely available on arXiv.

References

[MiUp17]

|

Michael Mitzenmacher and Eli Upfal: Probability and computing: Randomized algorithms and probabilistic analysis. 2nd. ed.: Cambridge University Press, 2017; ISBN 978-1107154889 |

|

[Tale22]

|

Nassim Nicholas Taleb: Statistical consequences of fat tails: Real world preasymptotics, epistemology, and applications. |