The Law of Demand explains how the quantity demanded of a commodity changes with changes in its price. It forms the foundation of consumer behavior in economics and is essential to understanding how markets function.

The Law of Demand states the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded, keeping other factors constant (ceteris paribus). This law is also known as the 'First Law of Purchase'.

In practical life, when the price of a product decreases, consumers usually buy more of it, and when the price rises, they tend to reduce consumption or switch to alternatives. This common behavior clearly demonstrates the Law of Demand in action.

Points to Remember

- The Law of Demand states that, everything else being constant, the quantity demanded of a good or service decreases as its price increases, and vice versa.

- The demand curve typically slopes downward from left to right, illustrating the negative correlation between price and quantity demanded.

- The Law of Demand applies both at the individual consumer level and across the entire market.

- The Law of Demand is often linked to the concept of diminishing marginal utility, which suggests that as consumers consume more units of a good, the additional satisfaction derived from each additional unit decreases.

Assumptions of Law of Demand

The Law of Demand is based on certain assumptions which ensure that only the effect of price on demand is studied. These are:

Income of the Consumer Remains Constant

The consumer’s income is assumed to stay the same. Any change in income would affect the purchasing power and alter the level of demand.

Tastes and Preferences Remain Constant

It is assumed that consumers’ tastes, habits, and preferences do not change during the period of study, as changes in them can influence demand.

Prices of Related Goods Remain Constant

The prices of substitute and complementary goods are taken as constant. A change in the price of related goods can shift demand even if the price of the commodity itself remains the same.

No Expectation of Future Price Changes

Consumers are assumed not to expect future changes in the price of a commodity. If they expect a price rise, they may buy more now; if they expect a fall, they may postpone purchases.

No Change in Population

The size and composition of the population are assumed to remain constant. Any increase or decrease in population would affect the total demand in the market.

No Change in Income Distribution

The distribution of income among different groups in society is assumed to remain unchanged. A redistribution of income could affect the demand for various goods.

No Change in Government Policies

It is assumed that government policies related to taxation, subsidies, or trade remain constant. A change in these policies could affect demand irrespective of price.

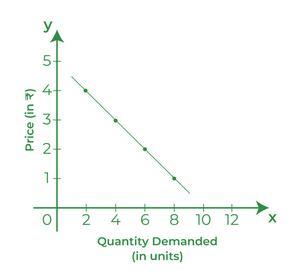

Graphical Presentation of Law of Demand

Let's take an example to understand the concept of the Law of Demand better.

Price (in ₹) | Quantity Demanded |

|---|

4 | 2 |

3 | 4 |

2 | 6 |

1 | 8 |

This can be visualised as:

The above table clearly shows that as the price of the commodity decreases, its quantity demanded increases. Also, the demand curve DD is sloping downwards from left to right, which means that there is an inverse relationship between the price and quantity demanded of the commodity.

Facts about Law of Demand

- One Sided: The Law of Demand explains only the effect of a change in price on quantity demanded, not the reverse.

- Inverse Relationship: It shows an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. When price increases, demand decreases, and when price decreases, demand increases.

- Qualitative, not Quantitative: The law states only the direction of change in demand, not the extent of that change.

- No Proportional Relationship: The change in demand is not always proportional to the change in price. It can vary in any proportion.

Derivation of Law of Demand

According to the Law of Demand, while keeping other factors constant, there is an inverse relationship between the demand and price of a commodity. It means that the demand for a commodity falls or increases with a rise or fall in its price, respectively. The inverse relationship between the price and demand for a commodity can be derived by:

1. Marginal Utility = Price Condition or Single Commodity Equilibrium Condition

According to this condition, a consumer buys only that much quantity of a commodity at which its Marginal Utility is equal to the Price. However, the Marginal Utility of a commodity can be more or less than its Price.

When Marginal Utility is less than the price of a commodity (MU<Price): The Marginal Utility of a commodity is less than the price when the price of the commodity increases. A rise in the price of the commodity discourages the consumer to purchase more of it, showing that a rise in the price of a good decreases its demand. The consumer in this buy will reduce the demand of the commodity until the Marginal Utility becomes equal to the price again.

When Marginal Utility is more than the price of a commodity (MU>Price): The Marginal Utility of a commodity is greater than the price when the price of the commodity falls. A fall in the price of the commodity encourages the consumer to purchase more of it, showing that a fall in the price of a good increases its demand. The consumer in this case will buy the commodity until the Marginal Utility falls and becomes equal to the price again.

Hence, it can be concluded that the demand for a commodity increases when its price falls, and vice-versa, i.e., there is an inverse relationship between the demand and price of a commodity.

2. Law of Equi-Marginal Utility

According to the law of equi-marginal utility, a consumer will be at equilibrium when he spends his limited income in a way that the ratios of the Marginal Utilities and the respective prices of the commodities are equal. The Marginal Utility falls as the consumption of the commodity increases.

In the case of two commodities, say X and Y, the equilibrium condition will be:

\frac{MU_x}{P_x}=\frac{MU_y}{P_y}.

Now, the effect of rise or fall in the price of the commodity on the equilibrium condition can be as follows:

When the price of Commodity X rises: If the price of commodity X increases, then \frac{MU_x}{P_x}<\frac{MU_y}{P_y}. It means that because of a rise in the price, the consumer is getting more Marginal Utility from Good Y as compared to Good X. So, he/she will buy more of Good Y and less of Good X, showing that the demand for Good X will reduce due to an increase in its price.

When the price of Commodity X falls: If the price of commodity X falls, then \frac{MU_x}{P_x}>\frac{MU_y}{P_y}. It means that because of a fall in the price, the consumer is getting more Marginal Utility from Good X as compared to Good Y. So, he/she will buy more of Good X and less of Good Y, showing that the demand for Good X will rise due to a fall in its price.

Hence, it can be concluded that the demand for a commodity increases when its price falls, and vice-versa, i.e., there is an inverse relationship between the demand and price of a commodity.

Reasons for Law of Demand

A consumer buys more of a commodity when its price is lower than a higher price because of the following reasons:

Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility states that as more and more units of a commodity is consumed, the utility derived by the consumer from each successive unit keeps decreasing. It means that the demand for a commodity depends on its utility.

Therefore, if a consumer gets more satisfaction from a commodity, he/she will pay more for it because of which the consumer will not be prepared to pay the same price for extra units of that commodity. Hence, the consumer will buy more of the commodity only when its price falls.

Example: As a person eats more slices of pizza, the satisfaction from each extra slice decreases, so they will buy more only if the price falls.

Substitution Effect

Substituting one commodity in place of another commodity when the former becomes relatively cheaper is known as the substitution effect. In other words, when the price of a commodity (let's say coffee) falls, it becomes relatively cheaper than its substitute (let's say tea), assuming that the price of the substitute (tea) does not change because of which the demand for the given commodity (coffee) increases.

Example: If the price of coffee falls while the price of tea remains the same, people may buy more coffee instead of tea.

Income Effect

When the real income of the consumer changes because of the change in the price of the given commodity, there is an effect on its demand. This effect on demand is known as Income Effect. In other words, when there is a fall in the price of the given commodity, it increases the purchasing power of the consumer, resulting in an increase in the ability of the consumer to buy more of it.

For example, suppose Sayeba's pocket money is ₹100, and she buys 10 ice-creams for ₹10 each from it. Now, if the price of the ice cream falls to ₹5 each, it will increase her purchasing power, and she can buy 20 ice-creams from her pocket money.

Additional Customers

When the price of a commodity falls, various new customers who could not purchase the commodity earlier due to its high price are now in a position to buy it. Besides new customers, the existing or old customers of the commodity will also start demanding more of the commodity because of the fall in price.

For example, if the price of pizza falls from ₹200 to ₹150, then many new customers who were not in a position to afford it earlier can now purchase it because of the fall in price. Also, the existing customers can now demand more pizza, resulting in an increase in its total demand.

Different Uses

Some commodities have different uses, among which some of them are more important, and the rest are less important. When the price of such commodities increases, consumers restrict its use to the most important purposes, increasing its demand for those purposes, and the demand for less important uses of the commodity gets reduced. However, when the price of the commodity reduces, consumers will use it for every purpose, whether it is important or not.

For example, Milk has various uses such as for drinking, making cheese, butter, sweets, etc. If the price of Ghee increases, then the consumers will restrict their use to the important purpose of drinking.

Also Read:

Exceptions to Law of Demand

The Law of Demand states that when the price of a commodity rises, its demand falls, and when the price falls, demand rises. However, there are certain exceptional cases where this law does not hold true. These are known as exceptions to the law of demand.

In certain situations, the Law of Demand does not hold true. In these cases, the quantity demanded may increase even when the price rises or decrease even when the price falls.

Giffen Goods

These are special types of inferior goods that form a large part of the consumption of low-income households. When the price of such goods rises, the real income of consumers falls, leaving them with less money to spend on costlier substitutes. Instead of reducing consumption, they end up buying more of the same good because it remains their only affordable option.

Example: Poor families may buy more rice or bread even when prices rise, as they can no longer afford superior foods like fruits or meat.

Fear of Shortage

When consumers anticipate a shortage of certain goods or expect prices to rise sharply in the future, they tend to purchase more of those goods immediately, even at higher prices. This behavior is driven by fear, uncertainty, or precaution rather than rational decision-making.

Example: During emergencies or natural disasters, people buy more of essential items like grains, medicines, or fuel, fearing scarcity in the future.

Status Symbol Goods

Some goods are bought not for their practical use but to reflect wealth, prestige, or social standing. For such luxury or prestige goods, a higher price often enhances their desirability, as it signals exclusivity and status. Thus, demand may increase with price.

Example: Luxury cars, designer handbags, and diamond jewelry are often bought to showcase affluence rather than for practical use.

Ignorance

Sometimes, consumers lack full knowledge of market conditions and believe that a higher price automatically means better quality or reliability. Due to this misconception, they may purchase a costlier item even when cheaper alternatives of similar quality are available. In such cases, the rise in price creates a false impression of superiority, leading to an increase in demand.

Example: A customer may prefer an expensive brand of perfume or electronics, assuming it to be superior in quality.

Necessities of Life

Goods that are essential for human survival or daily living are demanded irrespective of price changes. Even if prices rise sharply, people continue to buy them because these goods are unavoidable and form a part of basic consumption. The demand for such goods is highly inelastic, as there are no suitable substitutes that can replace them.

Example: Commodities like salt, cooking oil, medicines, and basic food items are purchased regardless of price fluctuations.

Change in Weather

The demand for seasonal goods is influenced more by climate and weather conditions than by price. During particular seasons, these goods become necessary for comfort, protection, or daily use, leading people to buy them even at higher prices. When the season ends, their demand automatically falls, no matter how low the prices drop.

Example: Woollen clothes and heaters in winter, or raincoats and umbrellas during the rainy season.

When certain products become fashionable or trendy, consumers purchase them to keep up with social trends, peer influence, or to maintain a modern image. The desire to appear stylish or accepted in society often outweighs the concern for price, causing demand to remain high even when prices rise. Once the trend fades or a new style replaces it, demand quickly drops even if the price becomes lower.

Example: Branded sneakers, trendy outfits, or the latest smartphone models continue to sell despite high prices when they’re in fashion.

Related Articles

Explore

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Consumer's Equilibrium

Chapter 3: Demand

Chapter 4: Elasticity of Demand

Chapter 5: Production Function: Returns to a Factor

Chapter 6: Concepts of Cost and Revenue

Chapter 7: Producer’s Equilibrium

Chapter 8: Theory of Supply

Chapter 9: Forms of Market

Chapter 10: Market Equilibrium under Perfect Competition